Burmese Jugglers in Imperial Britain

Posted on May 8, 2013 by jonathansaha

http://jonathansaha.wordpress.com/2013/05/08/burmese-jugglers-in-imperial-britain/

(Article reproduced here. Copyright Jonathan Saha)

Whilst I was doing my research for my PhD I came across a couple of letters sent to the Government of India regarding a troupe of Burmese jugglers who were stuck in the north-west of England having been abandoned by their employer in 1898. They had successfully toured Britain and Europe, but the promoter had apparently run out of cash, was unable to pay the arrears of wages owed to the performers, and had consequentially left them to find their own way home. In response some locals petitioned the government to provide financial aid to these destitute entertainers.

Burmese jugglers (if the newspaper reviews accurately reflected the audiences’ experiences) were well received in Britain during the nineteenth century. One reviewer in 1887 remarked how the juggling balls seemed to magically ‘grow out of the palms’ of the principal juggler’s hands, and how the ‘youngsters’ in the crowd cheered loudest for these performers. In 1896 audiences at the Crystal Palace in London were amazed by one Moung Toon’s abilities with a cane ball which ‘appeared to be endowed with human knowledge, so cunningly did it lend itself to the design of the performers.’ Moung Toon went on to tour in the United States the following year.

However, in 1900 it seems that he too found himself stuck. He had fallen in love with an English woman and she had agreed to marry him. Unfortunately, the clergyman refused to conduct the ceremony because Moung Toon’s manager had told him that Moung Toon already had a wife in Burma – although how true this claim was, I can’t currently verify. A rather uncharitable newspaper report claimed that ‘in his chagrin’ Moung Toon refused to perform any more, and made plans to return back to Burma.

These glimpses into the lives of Burmese jugglers are simultaneously stories of exploitation and solidarity. Their acts were popular and profitably marketed, although in both cases they did not see much in the way of monetary reward for their performances. In an unfamiliar land they were dependent on their promoters, who evidently couldn’t always be trusted. But there is also the support offered to the Burmese jugglers after they had been abandoned, as well as Moung Toon’s relationship with an English woman. These were unusual imperial circuits of travel and appear to have resulted in ties across the otherwise ubiquitous racial divide.

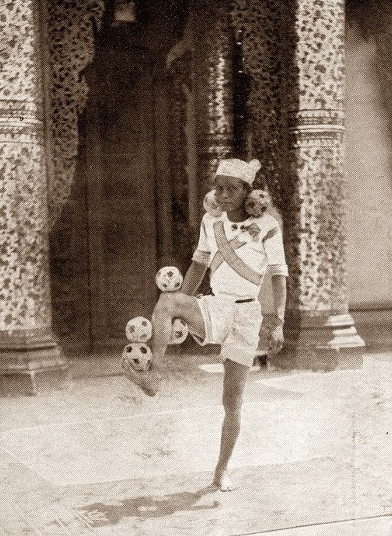

A picture of the juggler Maung Law Paw performing at Wembley in 1924 – I wonder what he made of interwar Britain?